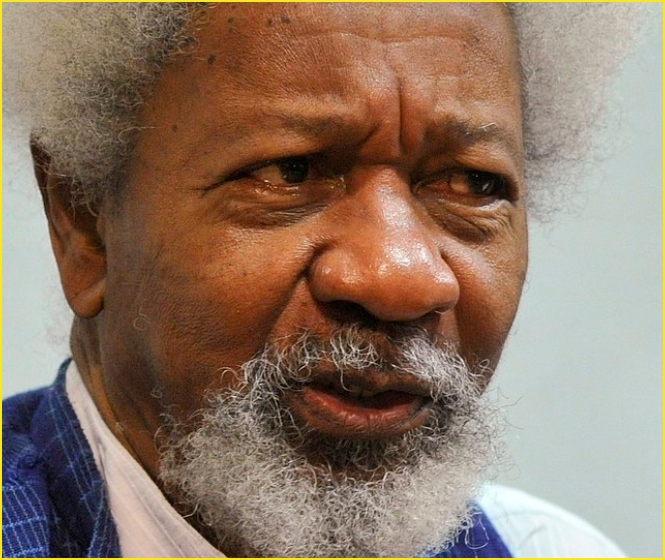

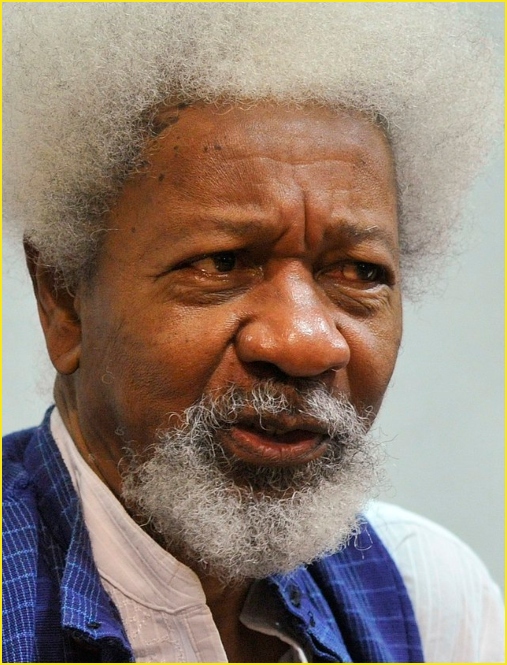

The Trump administration has revoked the U.S. visa of Nigerian Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka, marking yet another instance in what legal analysts are calling an increasingly politicized use of immigration power.

Soyinka, the first African to win the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1986, revealed the development during an event at Kongi’s Harvest Gallery in Lagos on Tuesday. Reading from a notice dated October 23, the 91-year-old author said the U.S. Consulate in Lagos requested he appear in person to have his visa “physically cancelled.”

“We request you bring your visa to the U.S. Consulate General Lagos for physical cancellation,” Soyinka quoted from the letter, describing it as a “rather curious love letter.”

Displaying his trademark wit, the literary icon joked, “Would any of you like to volunteer in my place? Take the passport for me? I’m a little bit busy and rushed.”

Soyinka said he was “content with the revocation”, noting it would merely limit his participation in U.S. literary and academic events. With a smile, he added:

“Maybe it’s about time also to write a play about Donald Trump.”

A Nobel Mind Meets a New Order

The revocation follows a pattern under President Trump’s second term, inaugurated in January, during which several prominent figures — including Nobel Peace Prize winner Oscar Arias of Costa Rica — have reportedly had their U.S. visas revoked.

Soyinka’s visa, originally issued during the Biden administration, appears to have been caught in a sweeping immigration review targeting individuals perceived as “bearing hostile attitudes” toward American “culture, government, and founding principles.”

Trump’s June proclamation on immigration stressed the need to safeguard the U.S. from “those who harbor adversarial beliefs or loyalties.” Critics argue that the language is legally vague and constitutionally troubling, potentially enabling punitive action against dissenting voices or foreign critics.

A human rights attorney in Washington, D.C., who asked not to be named, described the revocation as “a disturbing overreach that conflates criticism with hostility.” The attorney added: “Under U.S. constitutional norms, the government cannot lawfully retaliate against speech, even if it’s unflattering to the administration.”

The Literary Dissident

Soyinka, long celebrated for his fierce defense of free speech, is no stranger to political persecution. He was imprisoned in Nigeria during the civil war and famously continued writing in solitary confinement using toilet paper.

His international stature grew from his unwavering commitment to truth — and his criticisms have spared no one, including American presidents.

In 2017, following Trump’s first election victory, Soyinka publicly destroyed his U.S. green card in protest of what he called “the brutal and often unbelievable treatment of immigrants.” Speaking to The Atlantic at the time, he said, “As long as Trump is in charge, if I absolutely have to visit the United States, I prefer to go in the queue for a regular visa with others.”

That gesture cemented his reputation as a literary dissident unafraid of consequence.

Visa Revocations and Legal Precedent

From a legal perspective, the revocation raises broader questions about the discretionary powers of the executive branch in visa policy. While U.S. law grants presidents and the State Department wide latitude over immigration, scholars warn that politically motivated visa cancellations can cross into the territory of viewpoint discrimination, a potential violation of First Amendment principles.

Under 8 U.S.C. § 1201(i), the Secretary of State may revoke a visa “at any time, in his discretion,” with no requirement for prior notice or appeal rights for non-citizens. However, the doctrinal tension arises when such actions appear retaliatory for constitutionally protected expression.

The U.S. Supreme Court has historically deferred to executive power in foreign affairs (see Kleindienst v. Mandel, 408 U.S. 753 (1972)), but more recent jurisprudence — such as Zadvydas v. Davis, 533 U.S. 678 (2001) — has emphasized that even immigration decisions must align with “constitutional principles of liberty and fairness.”

Legal observers note that revoking visas from Nobel laureates, academics, and foreign dignitaries may invite diplomatic fallout and damage the U.S.’s reputation as a global defender of free thought.

A Broader Pattern of Retaliation

Former Costa Rican president Oscar Arias, who lost his visa in April, told NPR that U.S. officials cited his “ties to China” but admitted he suspected another reason: his public criticism of Trump.

“The president has a personality that is not open to criticism or disagreements,” Arias remarked.

A similar pattern emerged earlier this year when Colombian President Gustavo Petro saw his visa revoked after denouncing Israel’s war in Gaza during a U.N. speech, a move the U.S. State Department later labeled “reckless.”

You Can’t Silence Literature

Despite the diplomatic tensions, Soyinka struck a defiant tone in Lagos. “Governments have a way of papering things for their own survival,” he said. “The revocation of one visa, ten visas, a thousand visas will not affect the national interests of any astute leader.”

For Soyinka, whose works — from Death and the King’s Horseman to Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth — dissect tyranny and moral decay, the episode is less a personal loss than a reaffirmation of purpose.

“Books and all forms of writing are terror to those who wish to suppress the truth,” he once wrote.

Now, it seems, that terror still travels — even without a visa.