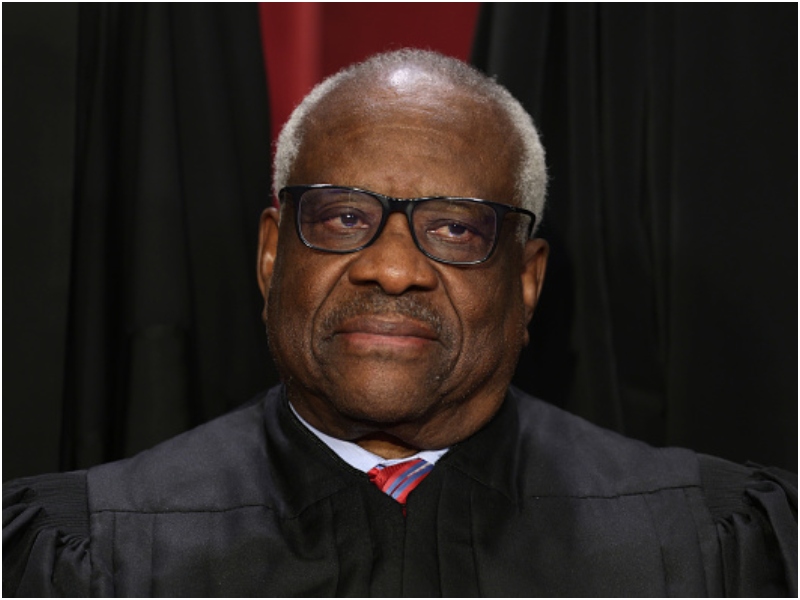

Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas is once again leading the charge to curtail a key provision of the landmark Voting Rights Act (VRA), a campaign he began over three decades ago.

With a now-conservative-leaning Supreme Court, his long-held views may be closer than ever to becoming binding precedent.

At the center of the current battle is a high-profile case, Louisiana v. Callais, which raises fundamental questions about Section 2 of the VRA—the provision that prohibits districting plans which dilute the voting power of racial minorities.

Though the case was argued in March, the justices announced on June 27, the final day of their term, that they had failed to reach a resolution and would reargue the case in the upcoming October session. That rare move signals potentially sweeping consequences, reminiscent of Citizens United v. FEC in 2010, where reargument preceded a major departure from precedent. The Court also stated it would issue further instructions regarding additional topics to be covered in the reargument.

In a separate six-page dissent, Justice Thomas urged the Court to go even further and declare that Section 2 itself violates the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. He reiterated his belief, first outlined in his 1994 dissent in Holder v. Hall, that the VRA has morphed from a remedial measure into a tool that divides political power along racial lines.

“Few devices could be better designed to exacerbate racial tensions,” he warned.

No other justice joined Thomas’ dissent in Callais, but several current justices have expressed varying degrees of agreement with his reasoning in past cases. Justice Neil Gorsuch has fully embraced Thomas’ criticism of race-based voting remedies, calling the Court’s jurisprudence on the matter a “disastrous misadventure.” Justices Samuel Alito and Amy Coney Barrett have supported a “race-neutral” interpretation of Section 2 in prior redistricting disputes.

In last year’s Allen v. Milligan, the four conservative justices dissented from Chief Justice John Roberts’ majority opinion upholding Section 2’s protections, despite Roberts’ own complex history with race-related rulings. In Shelby County v. Holder (2013), Roberts authored the opinion that dismantled another major VRA provision—preclearance requirements for states with histories of discrimination.

The Callais case stems from Louisiana’s 2022 congressional map, which included only one Black-majority district in a state where Black residents make up a third of the population. A federal court ordered the legislature to draw a second such district. When it did, to comply with Section 2 and protect incumbents like House Speaker Mike Johnson, a group of mostly White voters challenged the new map, alleging unconstitutional racial gerrymandering—a position echoing Thomas’ arguments.

During oral arguments in March, several justices, including Roberts and Gorsuch, questioned the legitimacy and compactness of the new second Black-majority district. Roberts called the district “a snake that runs from one end of the state to the other,” and Gorsuch raised constitutional concerns about using race at all in redistricting.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh floated the idea that there should be a “durational limit” on how long states may consider race in drawing voting districts under Section 2. That idea would represent a major shift from the Court’s current interpretation, which permits race-conscious remedies where racial polarization in voting persists.

Meanwhile, another VRA-related controversy looms over who can bring such lawsuits. While historically, private citizens and advocacy groups have enforced Section 2 through litigation, a May decision by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit held that only the U.S. Department of Justice can do so.

That ruling, now being appealed to the Supreme Court by Native American tribes in North Dakota, could eliminate private enforcement of the VRA in several states, particularly as the DOJ under Donald Trump reversed its historic role in protecting minority voting rights.

“The question of whether Section 2 may still be enforced by private parties is critical,” said lawyers representing the tribes in a filing last week. “Otherwise, millions of Americans would have fewer enforceable voting rights based solely on where they live.”

Legal analysts say that with Thomas’ persistent advocacy and a receptive bloc of justices, the coming term could prove pivotal for the future of voting rights in the United States. If the Court chooses to restrict or nullify Section 2, it would mark one of the most significant retreats from racial voting protections since the Act’s passage in 1965.

While Justice Thomas remains a lone voice in outright calling for Section 2 to be struck down, the Court’s willingness to revisit the Louisiana case—and potentially others—suggests the ground may be shifting.