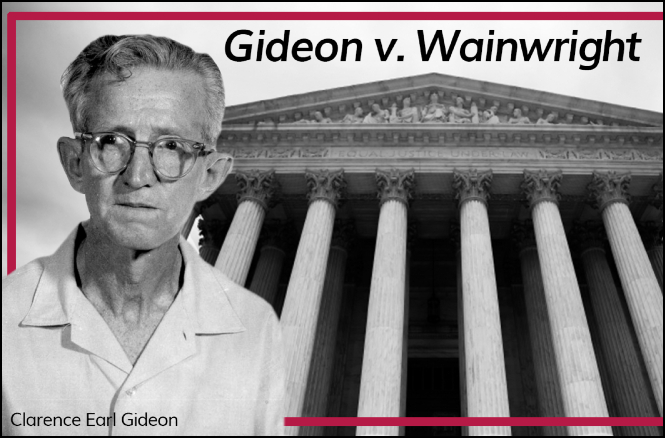

Case Study: Gideon v. Wainwright (1963) — Expanding the Right to Counsel in State Criminal Trials

Introduction

In the pantheon of landmark U.S. Supreme Court decisions, Gideon v. Wainwright stands as a powerful affirmation of due process and equal protection under the law.

Decided in 1963, the ruling cemented the principle that the Sixth Amendment’s guarantee of the right to legal counsel applies to defendants in state courts through the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause. At the center of this transformative case was an indigent Florida man named Clarence Earl Gideon, whose handwritten petition from a prison cell catalyzed a seismic shift in American criminal procedure.

Background: A Man Without a Lawyer

Clarence Earl Gideon, a drifter with an eighth-grade education and a long arrest record, was charged with breaking and entering the Bay Harbor Pool Hall in Panama City, Florida, in 1961. At his arraignment in a Florida state court, Gideon asked the judge to appoint him legal counsel because he could not afford an attorney. His request was denied based on Florida law at the time, which only provided court-appointed lawyers in capital cases.

Forced to represent himself, Gideon cross-examined witnesses, made opening statements, and attempted to present a defense. Unsurprisingly, he was convicted and sentenced to five years in prison.

The Legal Question

From his prison cell, Gideon filed a handwritten petition for a writ of certiorari to the U.S. Supreme Court. The central legal issue was:

Does the Sixth Amendment’s right to counsel in criminal cases extend to defendants in state courts via the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause?

This was not a new question. In Betts v. Brady (1942), the Court had ruled that the appointment of counsel for indigent defendants was not a fundamental right in all state cases—only when “special circumstances” existed. Gideon’s case directly challenged that precedent.

The Supreme Court’s Decision

On March 18, 1963, the Court issued a unanimous 9–0 decision, overturning Betts v. Brady and ruling in favor of Gideon.

Justice Hugo Black, writing for the Court, declared:

“In our adversary system of criminal justice, any person haled into court, who is too poor to hire a lawyer, cannot be assured a fair trial unless counsel is provided for him.”

This powerful statement laid the foundation for the modern public defender system.

The Court held that the right to counsel is a fundamental right, essential to a fair trial, and is applicable to the states through the Fourteenth Amendment.

Aftermath and Significance

Gideon’s conviction was overturned, and he was retried in Florida with the assistance of appointed counsel. This time, he was acquitted.

The implications of Gideon v. Wainwright were immediate and far-reaching:

- All states were now constitutionally required to provide attorneys to indigent defendants charged with felonies.

- The decision laid the groundwork for expanding the right to counsel in misdemeanor cases that could result in incarceration (see Argersinger v. Hamlin, 1972).

- It also sparked the nationwide development of public defender systems, which today serve as a crucial safeguard in ensuring equal justice under the law.

Criticism and Contemporary Challenges

While Gideon is hailed as a milestone in criminal justice, the public defender system it inspired faces ongoing challenges, including:

- Underfunding and excessive caseloads that can limit effectiveness.

- Disparities in legal representation quality, particularly in under-resourced jurisdictions.

- Systemic inequalities that persist despite the legal right to counsel.

Legal scholars continue to debate whether the promise of Gideon has been fully realized, or whether structural reforms are needed to truly deliver on its guarantee of fairness.

Conclusion

Gideon v. Wainwright is a textbook example of how the Supreme Court can serve as a corrective force in American democracy. From the isolated voice of a single prisoner came a ruling that reshaped the U.S. legal system, ensuring that no one would face the power of the state in a courtroom without the protection of legal counsel. In doing so, the Court affirmed that justice should not depend on one’s ability to pay.

The case continues to be cited in debates about criminal justice reform, the right to counsel, and the boundaries of constitutional protection. As we continue to grapple with issues of mass incarceration and due process, Gideon’s legacy reminds us that access to justice is not a privilege, but a right.