In the wake of the tragic 2015 mass shooting in San Bernardino, California, which left 14 people dead and 22 others seriously injured, a legal confrontation emerged that would reverberate across the realms of technology, civil liberties, and national security.

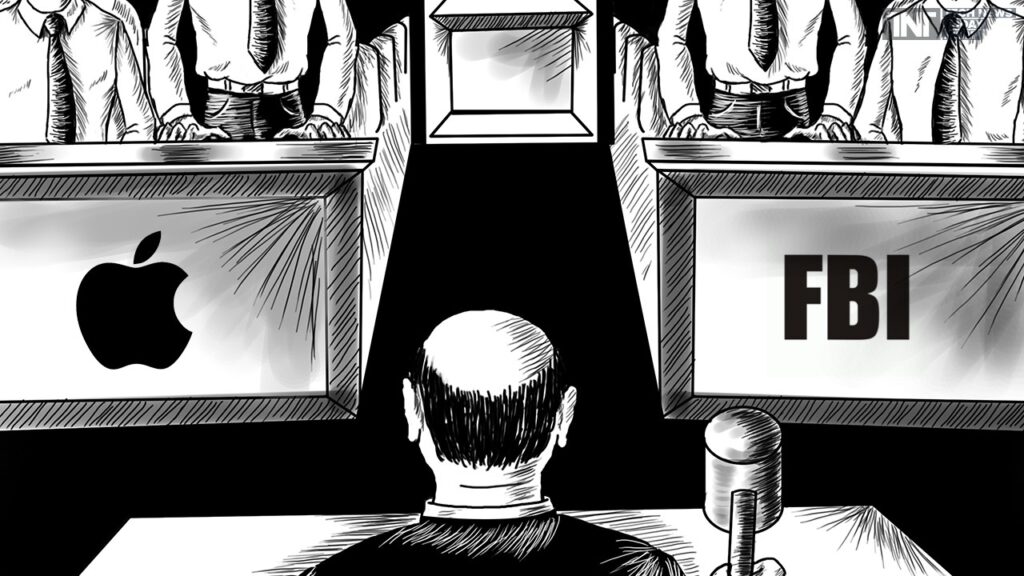

At the center: the locked iPhone 5c of Syed Rizwan Farook, one of the attackers, and a standoff between the FBI and Apple Inc. that would ignite a national debate over encryption, privacy, and government overreach.

The Shooting and the Seized Device

On December 2, 2015, Syed Rizwan Farook and his wife, Tashfeen Malik, carried out a mass shooting at a holiday party for Farook’s coworkers at the Inland Regional Center.

Both attackers were killed in a shootout with law enforcement later that day. In the ensuing investigation, the FBI recovered Farook’s government-issued iPhone, which was protected by Apple’s security features, including a 4-digit passcode and an automatic data wipe after 10 incorrect attempts.

Unable to access the device and fearing the loss of potentially critical intelligence, the FBI turned to Apple with a highly controversial demand: create software to bypass its own security protocols.

The Legal Weapon: The All Writs Act of 1789

On February 16, 2016, a federal magistrate judge ordered Apple to assist the FBI under the authority of the All Writs Act of 1789, a centuries-old statute that allows courts to issue orders necessary to aid their jurisdiction.

The Justice Department argued that Apple had the exclusive capability to unlock the iPhone and therefore had a legal and moral obligation to comply.

But Apple’s response stunned many in the legal and tech communities. CEO Tim Cook published an open letter opposing the order, stating that complying would set a “dangerous precedent” and potentially jeopardize the security of millions of iPhone users worldwide.

“The implications of the government’s demands are chilling,” Cook wrote. “If the government can use the All Writs Act to make it easier to unlock your iPhone, it would have the power to reach into anyone’s device to capture their data.”

A Precedent That Could Crack Privacy Wide Open

Apple argued that what the government was asking wasn’t simply about one device. Creating a custom tool — dubbed “GovtOS” by commentators — would amount to building a backdoor that could be used again and again.

The company maintained that complying would violate its First and Fifth Amendment rights and force it to undermine the privacy of its users.

The FBI countered that the request was narrow in scope, limited to a single device, and justified in the interest of national security.

Then-Director James Comey insisted the case was not about setting precedent but solving a real crime with potential links to future threats.

However, technologists and privacy advocates warned that the government’s framing was deceptive. Once created, such a tool could be repurposed, stolen, or demanded by other governments, opening a Pandora’s box that Apple could never shut.

A Swift and Surprising Twist

Before the court battle could play out fully, the Justice Department made a sudden move.

On March 28, 2016, it announced that it had successfully accessed the data on Farook’s phone with the help of an unnamed third party — later reported to be the Israeli firm Cellebrite — and dropped the case.

The legal showdown was abruptly over, but the questions it raised remain more relevant than ever.

Legacy: A Digital Rights Turning Point

Though Apple v. FBI did not reach a definitive legal resolution, its ripple effects endure in modern debates over digital privacy, government surveillance, and tech industry responsibility. The clash exposed the widening chasm between law enforcement’s desire for access and the tech world’s insistence on protecting user security through encryption.

The case also demonstrated how outdated legal tools — like the All Writs Act — are increasingly being stretched to fit the complexities of 21st-century technology. It has since been cited in policy debates around the world, influencing legislation on encryption, consumer data rights, and state surveillance capabilities.

Conclusion: A Battle Deferred, Not Resolved

The Apple v. FBI confrontation set the stage for an ongoing war between privacy and power — one where neither side is retreating. While Farook’s iPhone was ultimately unlocked without Apple’s help, the questions the case raised about how much control the government should have over encrypted data remain deeply unsettled.

With the rise of encrypted messaging platforms, biometric security, and increasingly powerful smartphones, the legal and ethical dilemmas of the digital age are only growing more complex. As technology continues to advance faster than legislation, another battle like Apple v. FBI is not just likely — it’s inevitable.