In the summer of 1971, the United States Supreme Court delivered a landmark ruling that would forever reshape the relationship between the press and the federal government.

The case, New York Times Co. v. United States, better known as the Pentagon Papers case, tested the limits of the First Amendment and government power. At the heart of the legal battle was a question both simple and monumental: Could the U.S. government prevent the media from publishing classified documents that exposed decades of deception about the Vietnam War?

The answer, in short, was no. The ruling was a decisive victory for press freedom—one that continues to influence debates over transparency, national security, and the public’s right to know.

A Secret History Exposed

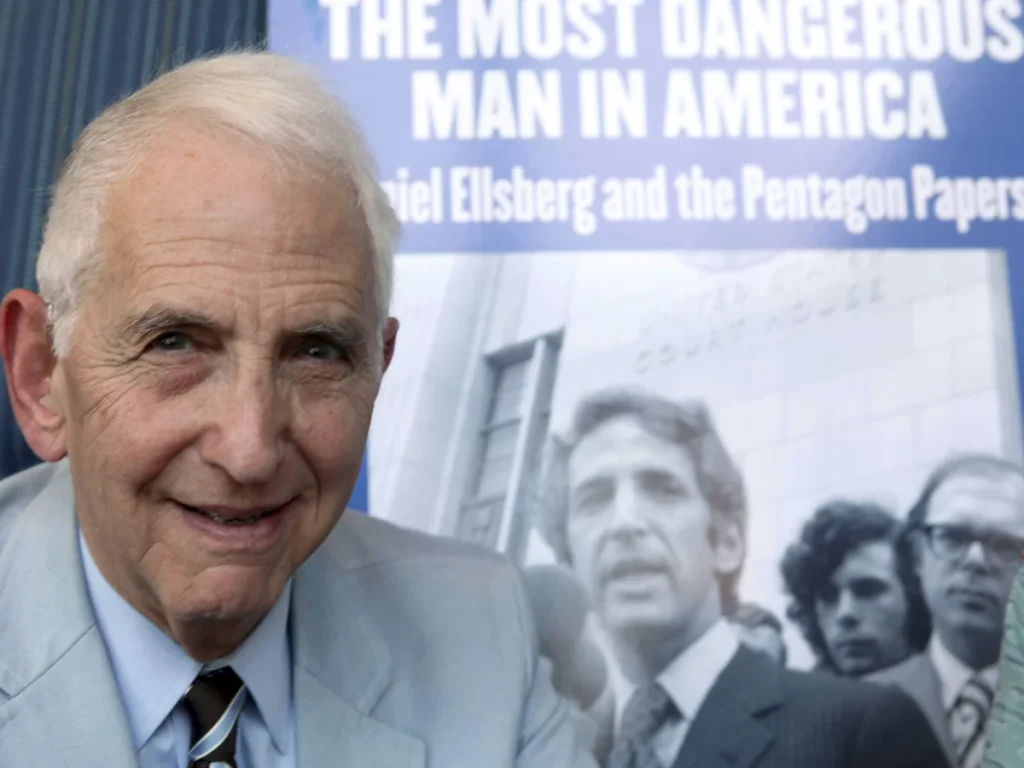

The saga began when Daniel Ellsberg, a former military analyst and consultant for the RAND Corporation, leaked a 7,000-page classified government study titled “Report of the Office of the Secretary of Defense Vietnam Task Force.” The report—later dubbed the Pentagon Papers—revealed that successive U.S. administrations had misled the public and Congress about the scope and goals of American involvement in Vietnam.

The documents showed that U.S. leaders, including Presidents Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon, had escalated the conflict even as they privately doubted the chances of success. The findings included bombings in Laos and Cambodia, covert operations, and deceptive strategies that contradicted official public statements.

Ellsberg believed the American people had a right to know the truth. In June 1971, he leaked the papers to The New York Times, which began publishing excerpts under the headline:

“Vietnam Archive: Pentagon Study Traces Three Decades of Growing U.S. Involvement.”

The Government Sues to Stop the Press

The Nixon administration swiftly moved to stop the presses, arguing that publication of the Pentagon Papers would cause “irreparable injury” to national security. The Department of Justice obtained a temporary restraining order against The New York Times, marking the first time in U.S. history that the federal government sought to impose prior restraint—the prohibition of speech before it occurs—on a newspaper.

Simultaneously, The Washington Post, which had also obtained a copy of the documents, prepared to publish its own series. When the government attempted to block them as well, the issue quickly escalated into a full-blown constitutional crisis.

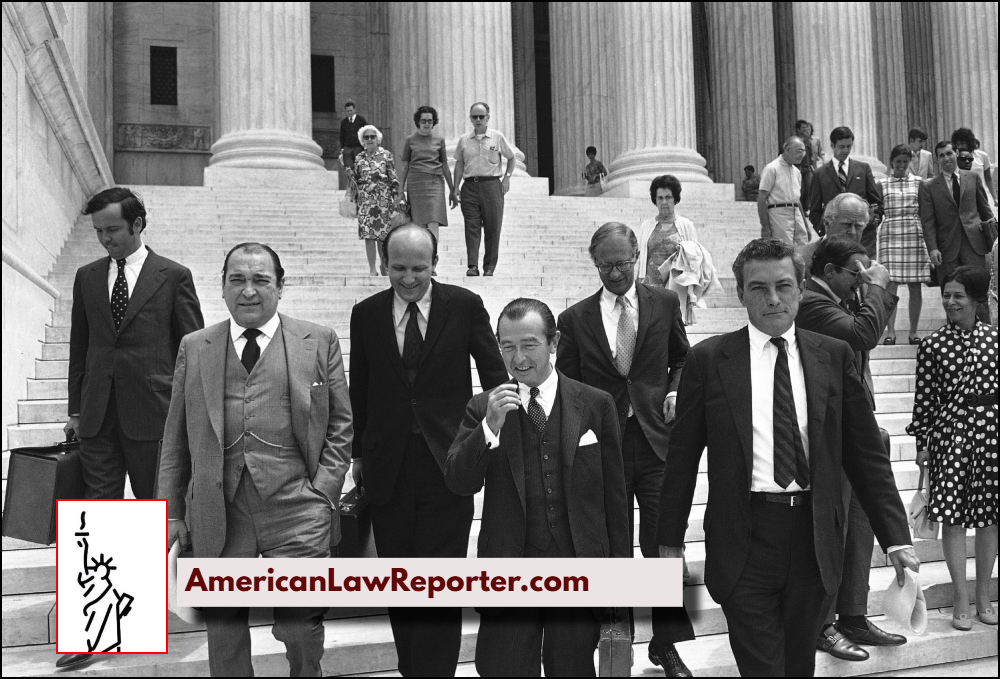

A Race to the Supreme Court

The legal battle moved swiftly through the lower courts. The Times and the Post, backed by other media outlets and civil liberties groups, argued that the First Amendment’s guarantee of a free press prohibited the government from suppressing publication of newsworthy material, even if it was classified.

The Nixon administration countered that national security interests justified prior restraint. Government attorneys claimed that publication could endanger military operations and diplomatic relations, although they failed to demonstrate specific, immediate harm.

Within weeks, the case reached the U.S. Supreme Court under a rare expedited schedule.

The Supreme Court’s Ruling: A Historic Win for Press Freedom

On June 30, 1971, the Supreme Court issued a 6–3 decision in favor of the newspapers. In a per curiam opinion, the Court held that the government had failed to meet the heavy burden required to justify prior restraint.

“Any system of prior restraints of expression comes to this Court bearing a heavy presumption against its constitutional validity,” the opinion read. “The Government thus carries a heavy burden of showing justification for the imposition of such a restraint.”

Each justice wrote a separate opinion, underscoring the complex constitutional questions involved. Justice Hugo Black, a fierce First Amendment advocate, wrote:

“The press was to serve the governed, not the governors. The Government’s power to censor the press was abolished so that the press would remain forever free to censure the Government.”

While Justices Burger, Harlan, and Blackmun dissented, they did not fundamentally reject press freedom—they argued instead for a more deliberate judicial process or deference to the executive branch in national security matters.

Aftermath and Legacy

Although the Pentagon Papers ruling didn’t declare that publishing classified information is always protected, it set a high bar for government censorship and reinforced the First Amendment’s vital role in democratic accountability.

Daniel Ellsberg was later charged under the Espionage Act of 1917, but his case was dismissed due to government misconduct, including illegal wiretapping and break-ins.

The case galvanized public distrust in government and led to broader investigations, including those that eventually brought down the Nixon administration. It also emboldened investigative journalism, paving the way for major exposés like the Watergate scandal.

Continuing Relevance

More than five decades later, the Pentagon Papers decision remains a cornerstone of press freedom jurisprudence. In recent years, it has been cited in legal disputes involving WikiLeaks, Edward Snowden, and other cases where national security and transparency collide.

Legal scholars and civil liberties advocates point to the case as a critical check on executive overreach.

“The principle that the government cannot muzzle the press unless it shows a real and immediate threat is more important than ever,” said a constitutional law professor. “The precedent set in 1971 is the reason why we still have a watchdog press today.”

Final Word

The Pentagon Papers case was more than a courtroom drama—it was a defining moment for American democracy. It reaffirmed that the free flow of information, even uncomfortable truths about the government, is not only protected but essential. In the words of Justice Stewart, “The only effective restraint upon executive policy and power may lie in an enlightened citizenry.”

The U.S. government tried to silence the press—and failed. And in that failure, the First Amendment stood tall.