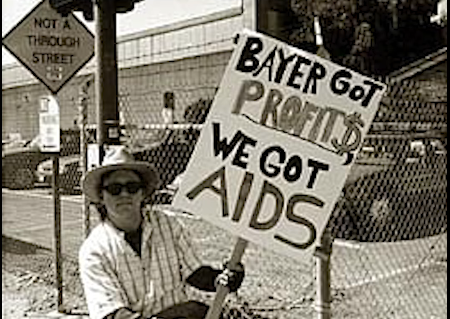

In one of the most damning pharmaceutical scandals to come to light, newly surfaced documents reveal that Cutter Biological, a division of Bayer, knowingly sold HIV-contaminated blood-clotting medicine to Asia and Latin America during the 1980s — even after introducing a safer, heat-treated product in the United States and Europe.

According to internal records obtained by The New York Times, Cutter continued to distribute the older version of its Factor VIII concentrate for over a year after launching the safer alternative in February 1984. Factor VIII, vital for hemophiliacs to prevent uncontrolled bleeding, was derived from plasma pooled from thousands of donors at a time when there was no effective screening for HIV.

The older, untreated product carried a high risk of transmitting the AIDS virus. While Bayer and other pharmaceutical companies eventually paid out approximately $600 million to settle lawsuits brought by American hemophiliacs, the toll overseas remains difficult to calculate. In Hong Kong and Taiwan alone, over 100 hemophiliacs contracted HIV after using Cutter’s unheated concentrate, many of whom later died.

In The UK, the scandal killed an estimated 2,400 people, prompting an investigation much later under Prime Minister Theresa May.

Documents suggest Cutter prioritized financial considerations over patient safety. Company memos indicate that executives sought to avoid losses from unsold inventory under fixed-price contracts and continued to manufacture the old product for months after the safer version became available. Cutter also instructed foreign distributors to “use up stocks” of the old concentrate before switching to the safer product.

A 1985 meeting between the FDA and blood-product manufacturers revealed further complicity. Federal officials reportedly urged companies to stop exporting the unsafe medicine but asked them to resolve the issue “quietly” to avoid alarming Congress, the medical community, or the public.

Bayer, in a written statement, defended its actions by asserting that some customers were skeptical of the new product’s effectiveness and that regulatory delays in some countries complicated the rollout. However, records from Taiwan’s health department indicate that Cutter delayed filing for approval of the safer product by more than a year.

Michael Baum, an attorney representing U.S. hemophiliacs, criticized Bayer’s profit-driven strategy:

“They needed to get the return for what they invested. They had processed the plasma, put it into vials, kept it in warehouses — and all that expense had already been incurred.”

While Bayer and three other U.S.-based blood-product companies — Armour Pharmaceutical, Baxter International, and Alpha Therapeutic — have faced civil litigation over the contaminated medicine, no criminal charges have resulted from the scandal to date.

The Cutter documents offer a rare and unsettling look into corporate decision-making during the early years of the AIDS epidemic. Despite mounting evidence connecting blood products to the transmission of HIV, Cutter aggressively marketed the older concentrate overseas to avoid financial losses — a decision that, according to victims and their families, had deadly consequences.

“They did not care about the lives in Asia,” said Li Wei-chun, whose son, a hemophiliac from Hong Kong, died of AIDS at the age of 23 after using Cutter’s product. “It was racial discrimination.”

The long-term impact of Cutter’s decisions remains a painful chapter in the global history of the AIDS crisis — one that continues to raise critical questions about corporate responsibility, regulatory oversight, and the value placed on human lives across different markets.