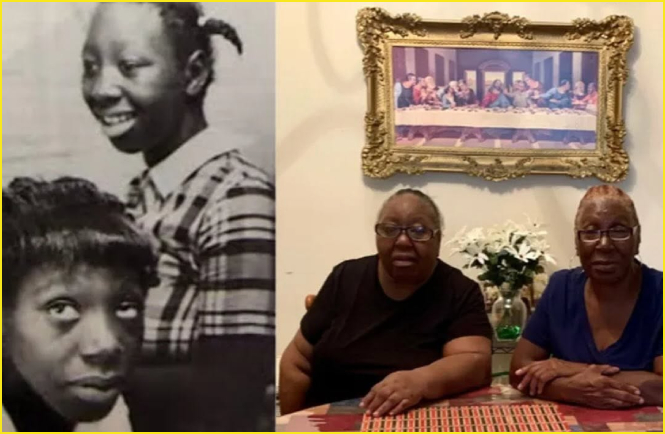

In 1973, in the heart of Montgomery, Alabama, two young Black sisters—Mary Alice and Minnie Relf—were subjected to an irreversible medical procedure they never consented to.

At just 14 and 12 years old, the girls were forcibly sterilized by a federally funded clinic.

Their mother, who could neither read nor write, had unknowingly signed a consent form with an “X,” believing it permitted the clinic to administer birth control shots to her daughters. What followed would unravel one of the most disturbing civil rights violations in U.S. medical history.

The Relf family’s harrowing experience became the centerpiece of Relf v. Weinberger, a class-action lawsuit filed in 1974 by the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC). The suit not only exposed the sisters’ traumatic experience, but it also unveiled a nationwide pattern of government-sanctioned sterilizations targeting society’s most vulnerable populations—poor people, people of color, individuals with disabilities, and young girls like Mary Alice and Minnie.

The SPLC’s legal action alleged constitutional violations under the Fourteenth Amendment and challenged the legality of using federal funds to carry out coercive sterilizations under Title XX of the Social Security Act. In doing so, it laid bare a systemic abuse of power operating beneath the guise of public health.

A Eugenic Blueprint

The Relf case did not emerge from a vacuum. It was part of a legacy deeply rooted in the eugenics movement that swept across America in the early 20th century. Under the guise of improving public welfare and reducing state burdens, eugenics advocates promoted sterilization laws as tools to curb the reproduction of those deemed “unfit.”

Between 1909 and the late 1970s, 32 states enacted laws authorizing involuntary sterilization, resulting in the sterilization of more than 60,000 people, many without informed consent. California alone accounted for over 20,000 sterilizations, targeting immigrants, the disabled, and poor women of color. In the South, the term “Mississippi appendectomies” emerged as a grim euphemism for medically unnecessary hysterectomies performed—often without consent—on Black women in teaching hospitals as practice for medical students.

As legal scholars and historians such as Dr. Alex Stern and William Deverell have documented, eugenics policies were upheld by pseudoscientific theories that linked poverty, criminality, and mental illness to genetics. These justifications not only fueled sterilization programs but also permeated public policy and medical ethics well into the modern era.

Federal Complicity and Legal Fallout

The legal revelations in Relf v. Weinberger were staggering. Court documents and investigative findings suggested that between 100,000 and 150,000 individuals were being sterilized annually under federally funded programs, often through coercion or deceit. Poor women—especially Black and Indigenous women—were frequently pressured into signing consent forms under threat of losing access to welfare benefits or essential healthcare services.

The case prompted immediate scrutiny of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW), leading to significant regulatory reforms, including the requirement of informed consent and the implementation of stricter guidelines surrounding sterilization procedures funded by the federal government.

But perhaps the most lasting impact of Relf v. Weinberger lies in its legal framing of reproductive rights as civil rights—a crucial pivot that would later inform broader movements for reproductive justice and bodily autonomy.

Compensation and the Long Arc of Justice

In the years since, only a handful of states have taken steps to redress the legacy of forced sterilization. In 2013, North Carolina became the first state to offer compensation to victims of its eugenics program, awarding $35,000 to 220 survivors. Virginia followed with a similar payout of $25,000 per survivor. In 2015, the U.S. Senate unanimously passed the Eugenics Compensation Act, acknowledging the harm inflicted by these programs, though no national reparations framework has been enacted to date.

Despite these gestures, survivors like the Relf sisters have yet to receive personal reparations. Their case remains a powerful legal precedent—cited in discussions around medical ethics, government accountability, and civil liberties.

Reproductive Justice in the 21st Century

Although Relf v. Weinberger took place half a century ago, the struggle for reproductive autonomy continues. As state legislatures across the country restrict access to abortion, contraception, and comprehensive reproductive care, advocates argue that the same power structures that enabled eugenic sterilizations are now resurfacing in new forms.

Deborah Reid of the National Health Law Program emphasizes the ongoing relevance of reproductive justice today:

“Reproductive justice is not just about choice—it’s about access, dignity, and the right of all individuals, especially women of color and low-income women, to make decisions about their own bodies free from coercion or control.”

Legal advocacy organizations now draw a direct line from the Relf case to current legal battles over abortion access, consent in detention facilities, and the treatment of women in the carceral system. Cases involving the forced sterilization of female inmates in California prisons as recently as 2010 echo the same disregard for autonomy that defined the Relf sisters’ ordeal.

Conclusion

The story of Mary Alice and Minnie Relf is more than a chilling tale from the past—it is a legal touchstone that continues to inform today’s debates on civil rights and medical ethics. It reminds us that justice delayed is not always justice denied—but it is often incomplete.

As the legal community revisits past cases of government overreach and seeks to chart a more ethical future, Relf v. Weinberger stands as a testament to what happens when law, medicine, and social policy collude to rob individuals of the most basic human right: the right to control one’s own body.