In the quaint village of Lintz, nestled in the rolling hills of County Durham, England, a timeless summer ritual unfolded for over seven decades: the gentle thwack of willow on leather, the cheers of young players, and the watchful eyes of elders under the sun.

This was the Lintz Cricket Club, a beloved community heartbeat where generations bonded over the noble game of cricket.

But in the 1970s, this idyllic scene collided with modern suburbia, sparking one of the most famous—and delightfully entertaining—cases in English legal history: Miller v Jackson.

It all began when new homes sprouted like daisies along the edge of the cricket ground. Mr. and Mrs. Miller, seeking a peaceful retreat, purchased one such property, blissfully unaware—or perhaps willfully ignoring—that their garden backed directly onto the boundary line. Soon, the Millers’ dream turned into a nightmare of flying cricket balls. Sixes soared over the fence with alarming regularity, denting flowerbeds, shattering greenhouse panes, and forcing the couple to huddle indoors during matches, hearts pounding at the risk of injury.

“Enough is enough,” they declared, hauling the cricket club’s chairman, Mr. Jackson, to court in 1977, alleging private nuisance and negligence. They demanded an injunction to halt the games altogether, arguing that the incessant invasions ruined their enjoyment of their home.

The case landed in the Court of Appeal, where the judges weighed the sanctity of property rights against the charm of village tradition. The majority—Geoffrey Lane and Cumming-Bruce LJJ—sided with the Millers on liability.

The cricket balls’ repeated incursions were deemed an unreasonable interference, a classic nuisance under English tort law. Crucially, they dismissed the club’s defense that the Millers had “come to the nuisance” by moving next to an established ground, affirming the principle from Sturges v Bridgman that prior existence doesn’t excuse ongoing harm. Negligence was also found, as the club could have taken more precautions, like higher fences.

Yet, in a twist that preserved the village’s spirit, the court refused the injunction. Shutting down the ground would devastate the community, they reasoned, outweighing the Millers’ grievances—especially since the couple benefited from the adjacent open space. Instead, damages were awarded for any proven losses, allowing cricket to continue amid the grumbles.

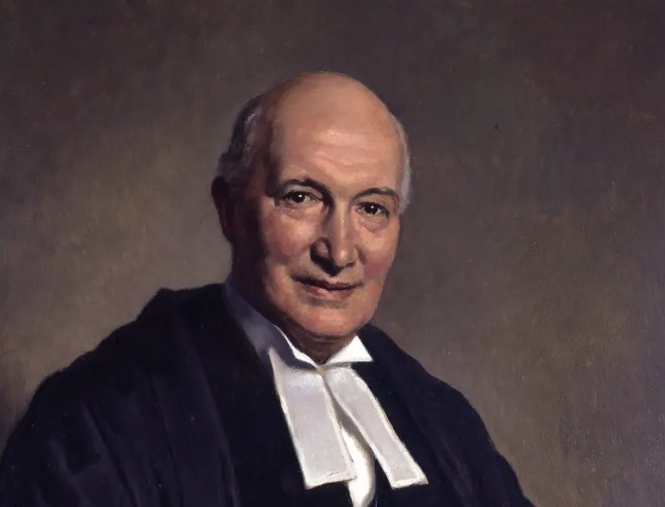

But oh, the real joy of Miller v Jackson lies in the dissenting judgment of Lord Denning, the Master of the Rolls, whose words have echoed through law schools like a perfectly timed cover drive. In a poetic ode to English summers, Denning lamented:

“In summertime village cricket is the delight of everyone. Nearly every village has its own cricket field where the young men play and the old men watch… The village green is the scene of many activities, but cricket is the chief.”

He argued passionately that the public interest in such wholesome pursuits should trump the private complaints of newcomers, effectively championing “coming to the nuisance” as a shield.

Though outvoted, Denning’s lyrical prose—evoking lazy afternoons, community bonds, and the essence of rural life—transformed a dry tort dispute into a cultural gem, making the case a staple in legal lore for its wit, humanity, and sheer readability.

Decades later, Miller v Jackson endures as a testament to the law’s balancing act: protecting individuals while cherishing traditions. It reminds us that justice isn’t always black and white—sometimes, it’s the green of a cricket pitch under a blue sky.