A growing number of African priests serving legally in the United States are finding themselves stranded abroad, detained, or denied re-entry under U.S. immigration procedures.

This is happening despite them holding valid documentation. Legal experts and church leaders warn that the trend exposes structural weaknesses in U.S. visa law governing religious workers and raises serious due-process and human-rights concerns.

One case drawing international attention is that of Father John K. Ojuok, a Kenyan Catholic priest who had been serving in the Diocese of Ogdensburg, New York, on an R-1 religious worker visa. In September, Fr. Ojuok travelled to Kenya to visit his mother and renew the visa stamp in his passport—a routine requirement under U.S. immigration rules. Although his interview at the U.S. Embassy reportedly went well, the visa stamp was later refused without explanation. He remains stranded in Kenya, unable to return to his parish.

In response, the Ogdensburg diocese has advised all foreign-born clergy to avoid international travel, underscoring growing anxiety within U.S. religious institutions over the unpredictability of immigration enforcement.

Fr. Ojuok’s case is not isolated. A Nigerian priest scheduled to begin ministry at St. Celestine Parish in Elmwood Park has been unable to secure a U.S. visa since June, despite meeting all formal requirements. In August 2025, Father Gustavo Santos, a Venezuelan priest serving in South Florida on a valid R-1 visa, was denied re-entry after foreign travel and was only allowed back following intervention by church authorities, immigration lawyers, and a federal judge. In Texas, Rev. James Eliud Ngahu Mwangi, a Kenyan Anglican priest with a work permit valid through 2029, was detained by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) over a prior visa overstay, despite his current lawful status.

Legal Framework Under Strain

Under U.S. immigration law, most foreign clergy enter on the R-1 nonimmigrant religious worker visa, which allows religious service for up to five years. After that period, the visa holder must leave the U.S. for at least one year before potentially returning, unless they qualify for permanent residence through the EB-4 “special immigrant religious worker” category.

However, visa backlogs and policy changes have created a legal bottleneck. Thousands of religious workers now face expiring R-1 status while their EB-4 green card applications remain pending. Immigration attorneys note that this gap leaves clergy vulnerable to removal, re-entry denials, or prolonged separation from their ministries—despite compliance with the law.

“This is a textbook example of lawful presence without meaningful legal security,” said a U.S.-based immigration lawyer who represents faith institutions. “The discretion exercised at embassies and ports of entry often lacks transparency, making judicial review difficult and creating due-process concerns.”

Broader Impact on Religious Institutions

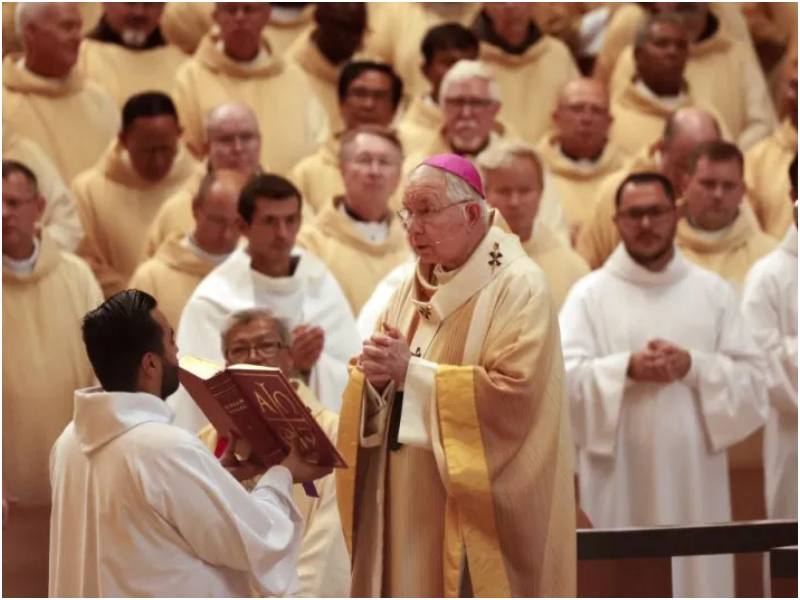

The legal uncertainty has practical consequences. According to the National Study of Catholic Priests (2022), about 24% of priests serving in the United States are foreign-born, many ordained outside the country. In rural and demographically declining dioceses, African and other international clergy are often essential to maintaining basic religious services.

At the same time, the number of U.S. priests has declined by roughly 40% since 1970, increasing institutional dependence on foreign clergy. Church leaders warn that sudden visa disruptions can leave parishes without pastoral leadership and overload already stretched local clergy.

In a special message on immigration, the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) expressed concern over what it described as “a climate of fear and anxiety around profiling and immigration enforcement,” lamenting that some immigrants have “arbitrarily lost their legal status.”

Enforcement, Discretion, and Equal Protection

Legal scholars situate these developments within a broader context of stricter immigration enforcement and expanded executive discretion, trends that intensified during the Trump administration and continue to affect visa adjudication. Critics argue that the opaque denial of visa renewals—without stated reasons—raises questions about equal protection, administrative fairness, and compliance with established immigration procedures.

Civil-rights advocates also point to the disproportionate impact on Black and brown immigrants, including African clergy, who often serve in the most under-resourced communities.

Legislative Response and Ongoing Litigation

The USCCB and other faith groups have thrown their support behind the Religious Workforce Protection Act, a bipartisan proposal that would allow religious workers with pending EB-4 applications to remain in the U.S. lawfully while awaiting permanent residency. A recent lawsuit filed by the Diocese of Paterson over religious worker visas was dropped amid expectations of a legislative or administrative fix, signaling growing recognition that immigration law has become a frontline legal issue for religious institutions.

For African dioceses that send clergy abroad, the situation has prompted calls for stronger legal safeguards, including pre-deployment immigration planning, access to legal counsel, and contingency protocols if visas are denied or revoked.

A Test for U.S. Immigration Law

As these cases accumulate, legal analysts say they highlight a fundamental tension in U.S. immigration policy: the reliance on foreign religious workers to sustain community life, paired with a legal framework that treats them as temporary and easily expendable.

For affected clergy and the communities they serve, the issue is no longer abstract. Routine travel for family emergencies, pastoral retreats, or official duties now carries the risk of prolonged exile—despite lawful status.

Whether Congress acts to close the legal gaps remains uncertain. What is clear, experts say, is that the current system exposes religious workers to arbitrary outcomes and places U.S. immigration law at odds with principles of due process, transparency, and human dignity.