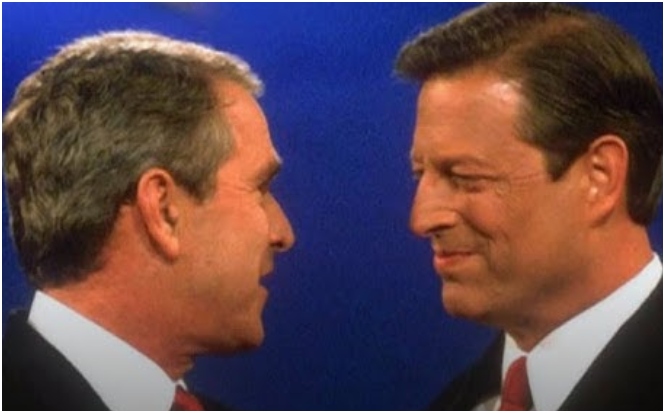

On December 12, 2000, the U.S. Supreme Court issued a 5–4 decision in Bush v. Gore, effectively resolving the presidential election in favor of Republican candidate George W. Bush over Democratic contender Vice President Al Gore.

The case, centered on contested vote recounts in Florida, marked an unprecedented moment in American legal and political history—one in which the judiciary played the decisive role in determining the presidency.

More than two decades later, Bush v. Gore remains one of the most controversial and consequential decisions ever issued by the Supreme Court. It highlighted the complex interplay between state election laws, federal constitutional protections, and the limits of judicial intervention. It also left a legacy of distrust and legal ambiguity that continues to influence how Americans think about voting rights, election integrity, and the role of the courts.

The Legal and Political Backdrop

The 2000 presidential election between George W. Bush and Al Gore came down to Florida, where the margin of victory was so narrow—just 537 votes out of nearly 6 million cast—that state law mandated an automatic machine recount.

That recount, however, quickly gave way to chaos. Ballots known as “hanging chads,” voter intent disputes, and discrepancies across Florida’s counties led to a series of lawsuits and counter-lawsuits in both state and federal courts. The Gore campaign sought a manual recount in four heavily Democratic counties, arguing that machine tabulations had failed to count thousands of legally cast votes.

Meanwhile, the Bush campaign contended that selective recounts violated principles of fairness and uniformity. As legal battles escalated, the Florida Supreme Court ordered a statewide manual recount of undervotes—ballots that had not registered a vote for president due to incomplete or ambiguous marks.

The U.S. Supreme Court intervened twice. First, it halted the manual recount on December 9, 2000, to consider whether the process violated the Constitution. Then, on December 12, the Court issued its final ruling in Bush v. Gore, ending the recount and effectively delivering Florida’s 25 electoral votes—and the presidency—to George W. Bush.

The Constitutional Arguments

At the heart of Bush v. Gore was the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The majority opinion, per curiam (unsigned), held that the lack of uniform standards for the manual recount across Florida counties violated voters’ constitutional rights.

“The recount mechanisms implemented in response to the decisions of the Florida Supreme Court do not satisfy the minimum requirement for non-arbitrary treatment of voters,” the Court said.

The decision emphasized that different counties were applying different standards to determine voter intent—for example, whether a partially punched chad constituted a valid vote. This discrepancy, according to the majority, amounted to unequal treatment under the law.

Crucially, the Court concluded that there was insufficient time to conduct a new, constitutionally valid recount before the December 12 deadline for certifying electors under federal law. Thus, the recounts were stopped, and the certified result favoring Bush stood.

A Deeply Divided Court

The Court split 5–4 along ideological lines. Chief Justice William Rehnquist and Justices Antonin Scalia, Sandra Day O’Connor, Anthony Kennedy, and Clarence Thomas formed the majority. Justices John Paul Stevens, David Souter, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and Stephen Breyer dissented, each writing separately.

In a biting dissent, Justice Stevens lamented the impact of the decision on public confidence in the judiciary. “Although we may never know with complete certainty the identity of the winner of this year’s presidential election, the identity of the loser is perfectly clear. It is the Nation’s confidence in the judge as an impartial guardian of the rule of law,” he wrote.

Justice Breyer warned that the majority had overstepped the proper boundaries of judicial restraint, effectively deciding an election outcome that should have remained in the democratic process.

The majority took the unusual step of stating that its ruling was “limited to the present circumstances” and not intended to serve as precedent. Still, legal scholars have debated for years whether the decision undermined the Court’s institutional credibility or was a necessary intervention in an unprecedented electoral crisis.

Legal and Political Consequences

The immediate consequence of Bush v. Gore was clear: George W. Bush became the 43rd President of the United States. Al Gore conceded the next day, saying, “While I strongly disagree with the Court’s decision, I accept it.”

But the longer-term impact reverberates still. The case is often cited in debates about judicial overreach, partisanship on the Supreme Court, and the reliability of election systems. It also laid the groundwork for subsequent litigation battles over voter ID laws, redistricting, and voting access—especially those invoking the Equal Protection Clause.

In the years following the decision, some legal scholars praised the Court for bringing finality to an explosive national crisis. Others argue it fundamentally damaged the Court’s legitimacy by appearing to hand the presidency to one political party.

Moreover, Bush v. Gore altered how campaigns prepare for contested elections. Legal teams are now more proactive in anticipating litigation, and state election laws have been subjected to greater scrutiny. The case has become a template—and a warning—for how legal contests can intersect with democracy.

Legacy and Continued Relevance

Although the Supreme Court emphasized that Bush v. Gore should not be viewed as precedent, its influence has persisted. The decision has been cited in other voting rights cases, including those involving redistricting and access to absentee ballots.

It has also shaped public expectations about the Court’s role in elections. As recently as the 2020 presidential contest between Donald Trump and Joe Biden, the specter of Bush v. Gore loomed large. Dozens of lawsuits were filed contesting results in swing states, with many hoping the Supreme Court would once again intervene. This time, the Court declined to take up any of the major post-election challenges.

Yet the fact that so many Americans looked to the judiciary to resolve election disputes underscores how Bush v. Gore transformed the perception of courts from neutral arbiters to potential kingmakers in presidential politics.

Conclusion

Bush v. Gore was more than a legal decision—it was a defining moment in American history. It tested the limits of judicial power, redefined the role of the Supreme Court in electoral politics, and reshaped the legal and political landscape for decades to come.

The case remains a lightning rod in debates over election integrity, judicial impartiality, and constitutional interpretation. Whether seen as a necessary end to a national crisis or a troubling assertion of judicial power, Bush v. Gore stands as a sobering reminder that in the most pivotal moments, the courtroom—not the ballot box—can decide the fate of a presidency.