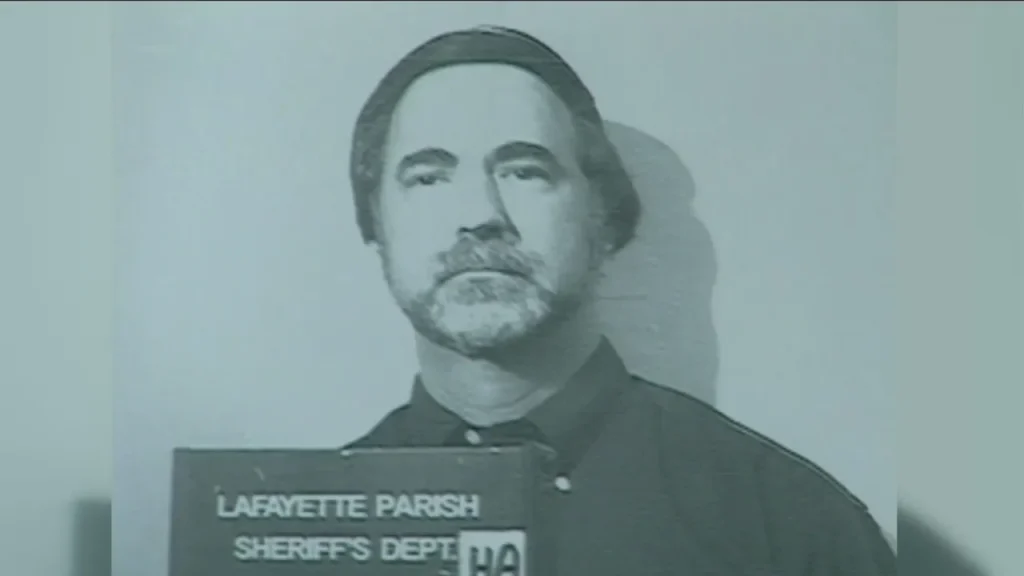

By all accounts, Dr. Richard J. Schmidt was a trusted gastroenterologist. Respected. Experienced. But what happened in the sleepy town of Lafayette, Louisiana in the 1990s would turn him into the center of one of the most shocking and innovative criminal trials in American history.

This isn’t your run-of-the-mill courtroom drama. No, the tale of Dr. Schmidt involves love gone sour, medical betrayal, and cutting-edge science that would rewrite the rulebook on forensic investigations.

This case has everything: heartbreak, syringes, subterfuge—and, ultimately, a precedent-setting conviction that turned viruses into witnesses.

Love, Lies, and Lethal Injections

In 1994, nurse Janice Trahan, then in her mid-thirties, was in the process of untangling herself from a long-term affair with her boss, Dr. Richard Schmidt. The relationship had been rocky, filled with false promises and delayed divorces. Like many stories of secret love, it ended with bitterness—but this one would spiral into something far more sinister.

Janice wanted out. She was moving on. But Schmidt didn’t take rejection lightly.

One summer evening, under the pretense of giving her a vitamin B-12 shot, Schmidt injected her with a substance she could not identify. The sting was sharp. But what came later was sharper still: Janice began experiencing strange symptoms—fatigue, rashes, night sweats. She was eventually diagnosed with HIV. Soon after, she also tested positive for hepatitis C.

This wasn’t just a medical mystery. It was an emotional grenade. Trahan suspected foul play. She wasn’t an IV drug user, and she hadn’t had other sexual partners in years. She made the bold accusation: her former lover had injected her with HIV.

Cue the scientific cavalry.

The Virus That Testified

Prosecutors were initially stumped. How do you prove someone intentionally injected another person with HIV? There was no camera, no witness, no syringe recovered. Just a chilling hunch and a very sick woman.

But what Janice did have was a virus. Or rather, multiple copies of it, replicating inside her body.

Enter the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and an ambitious virologist named Dr. Michael Metzker. Using cutting-edge phylogenetic analysis—essentially a family tree for viruses—scientists compared the HIV strain infecting Janice to strains found in Schmidt’s patients.

After combing through dozens of samples, they found a near-identical match: the virus from one of Schmidt’s HIV-positive patients.

In a twist worthy of a thriller novel, Schmidt had drawn blood from one of his own patients—without that person’s knowledge—and used the virus as a weapon. The hepatitis C infection? That strain matched another one of his patients. Double dose of evidence.

For the first time in U.S. history, HIV molecular fingerprinting was allowed in a court of law.

Trial, Conviction, and a Medical Betrayal Unveiled

The courtroom was captivated. Experts testified. DNA sequences were analyzed. Phylogenetic trees lit up monitors. The virus had done something incredible: it had told its story.

In 1998, Richard J. Schmidt was convicted of attempted second-degree murder and sentenced to 50 years in prison without parole. The case made national headlines—not just because of the shocking betrayal of a doctor against a nurse, but because it introduced a new era of molecular forensics.

Janice survived. Physically, she would live with her diagnosis forever. But in many interviews, she emphasized that what hurt the most wasn’t the virus—it was the betrayal.

The Science of Justice

The Schmidt case was groundbreaking because it was one of the first to use viral genetic evidence in a criminal trial. Before this, forensic science had been dominated by blood types, fingerprints, and—later—DNA. But viruses? That was uncharted territory.

The HIV virus mutates rapidly, but not randomly. Scientists could trace its path through hosts, identifying “clusters” of infection. This meant they could tell whether two people were likely connected through transmission—like branches of the same viral family tree.

This trial opened doors to the use of epidemiological forensics in everything from HIV transmission to bioterrorism investigations.

Legacy, Lessons, and Lethal Lessons in Love

Dr. Richard Schmidt who died in prison in 2023, is now a name etched in both legal and scientific history. His conviction proved that science could unveil not just what happened—but who did it—even when the tools were microscopic strands of RNA.

The case also serves as a haunting reminder of how power, access, and manipulation can turn someone’s profession into a weapon. Here was a doctor—someone trained to heal—who used his medical expertise to harm.

And Janice? She became a fierce advocate, speaking out about medical ethics, HIV awareness, and the need to believe victims even when the crime seems “unthinkable.” Her courage, and the virus in her bloodstream, helped set a precedent that’s been used to pursue justice ever since.