The case of People v. The Klan—more formally known as Donald v. United Klans of America—stands as a pivotal moment in American legal history, marking one of the most significant legal victories against the Ku Klux Klan (KKK).

This lawsuit, filed in 1984 by Beulah Mae Donald, the mother of lynching victim Michael Donald, not only secured justice for her son but also set a precedent for using civil litigation to dismantle white supremacist organizations.

This case was more than just a legal battle—it was a turning point in civil rights law, demonstrating that hate groups could be held financially accountable for their acts of terror. The lawsuit resulted in a $7 million judgment against the United Klans of America, effectively bankrupting the organization.

Case Background: The Lynching of Michael Donald

On March 21, 1981, 19-year-old Michael Donald was abducted in Mobile, Alabama, by two members of the United Klans of America, Henry Hays and James “Tiger” Knowles. The murder was a response to a mistrial in the case of a Black man accused of killing a white police officer, and the Klansmen sought to send a message of racial terror.

Hays and Knowles beat Michael Donald, cut his throat, and hanged his body from a tree. That same night, other Klan members burned a cross outside the Mobile County courthouse in celebration. Initially, local police dismissed the murder as drug-related, but Beulah Mae Donald pushed for a federal investigation, which led to Hays and Knowles being arrested and convicted of capital murder.

Hays was sentenced to death and executed in 1997, becoming the first white person in Alabama to be executed for killing a Black person since 1913. Knowles pleaded guilty and testified against Hays, receiving a life sentence.

The Civil Lawsuit: Holding the Klan Accountable

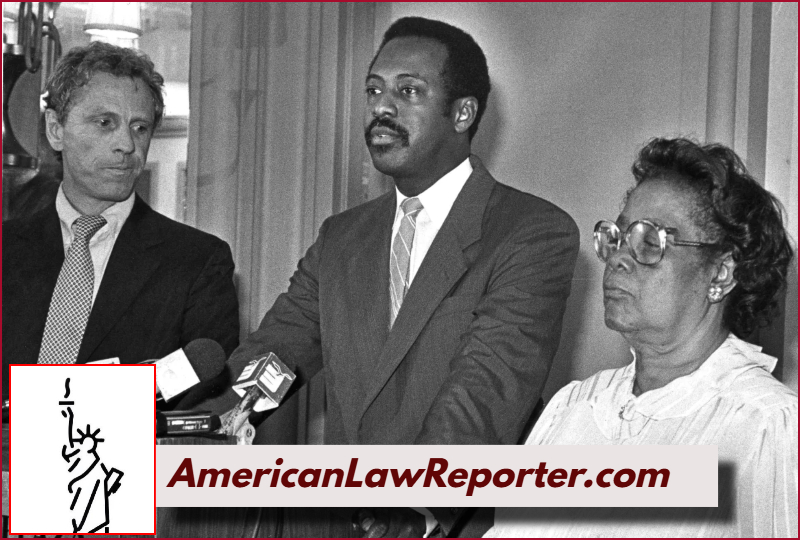

While the criminal convictions brought some measure of justice, Beulah Mae Donald, with the assistance of the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), sought to hold the Klan itself accountable. In 1984, she filed a wrongful death lawsuit against the United Klans of America under the legal theory that the organization was responsible for her son’s murder.

The SPLC, led by attorney Morris Dees, argued that the Klan’s leadership bore direct responsibility for the actions of its members. The lawsuit was based on the doctrine of respondeat superior, which holds organizations liable for the actions of their agents. The legal strategy focused on proving that the Klan had orchestrated the murder as part of its campaign of racial terror.

Legal Precedents and Arguments

The lawsuit relied on a mix of federal civil rights laws and state wrongful death claims, including:

- 42 U.S.C. § 1985(3) (the Civil Rights Act of 1871, also known as the Ku Klux Klan Act), which allows victims of racial violence to sue conspirators in federal court.

- Alabama wrongful death statutes, which permitted Beulah Mae Donald to seek damages for her son’s murder.

- The use of civil RICO (Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act) principles, though not formally charged under RICO, to demonstrate that the Klan operated as an organized criminal enterprise engaged in racist violence.

During the trial, evidence was presented showing that the Klan had a history of inciting violence and that Hays and Knowles were acting on its behalf. The jury was convinced that the Klan leadership, including Imperial Wizard Robert Shelton, played a direct role in fostering the culture of violence that led to Michael Donald’s lynching.

The Verdict and Its Impact

In 1987, an all-white jury in Alabama delivered a historic verdict, awarding Beulah Mae Donald $7 million in damages.

The judgment financially crippled the United Klans of America, forcing them to turn over their headquarters in Tuscaloosa, which was sold to help pay the damages.

The ruling effectively dismantled the United Klans of America and set a precedent for holding hate groups accountable through civil litigation. It also encouraged further lawsuits against white supremacist organizations, demonstrating that these groups could not operate with impunity.

Legal and Social Significance

The People v. The Klan case remains one of the most significant legal actions in the fight against racial terrorism in America. It showcased the power of civil litigation as a tool for justice, particularly when criminal convictions alone were not enough.

Key Legal Implications

- Civil Lawsuits as a Tool Against Hate Groups

The case demonstrated that hate groups could be sued into bankruptcy, a strategy that has since been used against other white supremacist organizations, including the Aryan Nations and the Charlottesville Unite the Right rally organizers. - Expanding the Use of the KKK Act

Donald v. United Klans of America reinforced the applicability of the Civil Rights Act of 1871 in modern hate crime cases, paving the way for other victims to seek justice under similar statutes. - Financial Consequences for White Supremacist Organizations

The verdict showed that racist violence could have severe economic consequences, leading to a decline in organized Klan activity.

Legacy and Continuing Impact

Beulah Mae Donald’s courageous fight for justice reshaped civil rights law. Her case is now studied in law schools and serves as a model for modern litigation against hate groups. Organizations like the SPLC continue to use similar strategies to combat racial extremism.

The principles established in People v. The Klan were instrumental in later lawsuits, including the 2017 lawsuit against white supremacist leaders responsible for the violence in Charlottesville, Virginia, which resulted in a $26 million judgment.

Conclusion

The case of People v. The Klan is a testament to the power of the legal system in the fight against racial violence and hate groups. Beulah Mae Donald’s perseverance not only secured justice for her son but also helped dismantle one of the most dangerous white supremacist organizations in the country.

Her legacy continues to inspire legal battles against hate, proving that even in the face of immense tragedy, the law can be a powerful tool for justice.