Before Georgia’s Lake Lanier became a popular recreation site, a thriving Black community stood in its place.

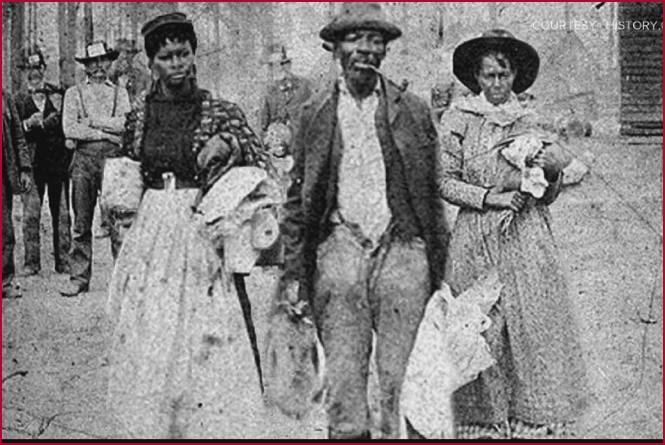

Oscarville, established in the late 1800s during Reconstruction, was a self-sufficient town where Black farmers, carpenters, blacksmiths, and bricklayers flourished despite the racial tensions of the era.

Its economic success stood in stark contrast to the struggles of other parts of Georgia.

However, in 1912, that prosperity came to a violent and tragic end—one rooted in racial terror and legal impunity.

The False Accusation That Led to Mass Racial Violence

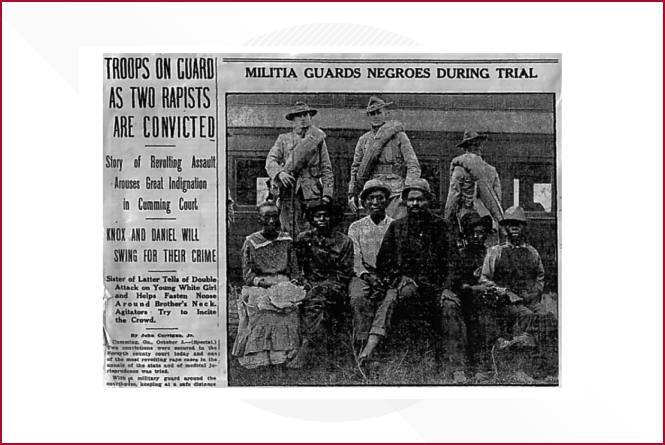

The destruction of Oscarville began with the discovery of Mae Crow, a 19-year-old white woman, who was found dead in the woods near the town. Although the details surrounding her death remain uncertain, Black men from the community were immediately accused of her assault and murder.

What followed was a coordinated, racist campaign of terror. White mobs, known as “night riders,” descended upon Oscarville, brutally driving out its Black residents through intimidation, arson, and murder.

Filmmaker Bob Mackey, who is chronicling these events in an upcoming television series, describes the violence as systematic and calculated.

“They woke up to fires outside, firebombs thrown in the church,” Mackey explained. “And the church was the heart of the community—where everyone sought safety. That’s where the mobs struck first.”

Survivors of the massacre recount stories of entire families fleeing for their lives. Some attempted to cross the Chattahoochee River to safety in nearby Gainesville, only to be pursued by armed white supremacists. Many did not survive.

Erased From History, Covered by Water

In the aftermath, white residents seized Oscarville’s abandoned land. Some of the very same Black farmers who had pioneered poultry farming in the region were dispossessed, paving the way for Gainesville to later become the “Poultry Capital of the World.”

Then, decades later, the erasure of Oscarville became complete. In the 1950s, the U.S. government constructed Buford Dam, flooding the area and forming what is now known as Lake Lanier.

Underneath its waters lay the remnants of a once-thriving Black town, a history intentionally submerged both physically and within public consciousness.

A Call for Recognition and Justice

For descendants of Oscarville’s displaced residents, the loss is personal. George Rucker, who traced his lineage four generations back to the town, shares his great-grandfather’s harrowing story.

“When the night riders came through, they had to leave everything,” Rucker said. “My grandfather had 100 acres of land. He lost everything.”

Rucker’s family was forced to flee to Gainesville, but not all of his relatives survived the violent expulsion.

“When they reached the bridge, they had two choices: swim or drown,” he said. “Most didn’t make it.”

Despite the devastation, Rucker’s great-grandfather, Byrd Oliver, persevered. He later helped establish the Beulah Rucker House-School, a historic educational institution in Gainesville.

The Legal Silence on Racial Displacement

What happened in Oscarville mirrors countless other racial massacres across America, including the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre and the destruction of Rosewood, Florida. Yet, unlike some cases that have gained national attention, Oscarville remains largely overlooked.

Historians and activists argue that the erasure of Oscarville is part of a broader pattern of historical suppression. Properties stolen from Black families were never returned, and no legal action was ever taken against the perpetrators of the violence.

“The fact that these families lost their land and generational wealth with no restitution is an ongoing injustice,” said historian Lisa Crosby. “Oscarville’s story is a testament to how racial violence was used to enforce economic disenfranchisement.”

Resurfacing the Truth

As awareness grows, filmmakers and historians are working to ensure Oscarville’s story is told. An upcoming documentary, led by executive producers William Eric Bush-Anderson, Cindy Kunz-Anderson, and Ali Ashtigo, aims to shed light on the buried history of Lake Lanier.

“There was another Black Wall Street before it was taken away,” Bush-Anderson said. “People need to know the truth.”

Meanwhile, Lake Lanier remains infamous—not only for its dark past but for its high rate of drownings. Some locals believe the spirits of Oscarville’s victims still haunt the waters, a chilling reminder of the injustice that has never been rectified.

For descendants like Rucker, the fight for recognition continues.

“If this could happen to Oscarville, it could happen anywhere,” he said. “And if we don’t acknowledge the truth, it can happen again.”

The destruction of Oscarville raises critical legal and ethical questions about racial violence, property theft, and historical accountability. Without legal restitution, the families of Oscarville remain dispossessed, highlighting the long-standing failure of the justice system to address hate crimes and racially motivated land dispossession.