When Jennifer Juan attempted to cast her ballot in Arizona’s state primary in July, she spent an hour sorting through documents to convince poll workers of her eligibility. This challenge reflects a widespread issue for many Native American voters like Juan.

As a registered voter on the Tohono O’odham Nation reservation, Juan lacks a physical address. Instead, her voting record provides a vague description of her home’s location—near milepost 7 on Indian Route 19, specifically the 53rd house built in Cold Fields Village. This situation made it difficult for her to meet the requirement of presenting documents that include a specific address, especially since some of her identification listed only a P.O. box, which many reservation residents use for receiving mail.

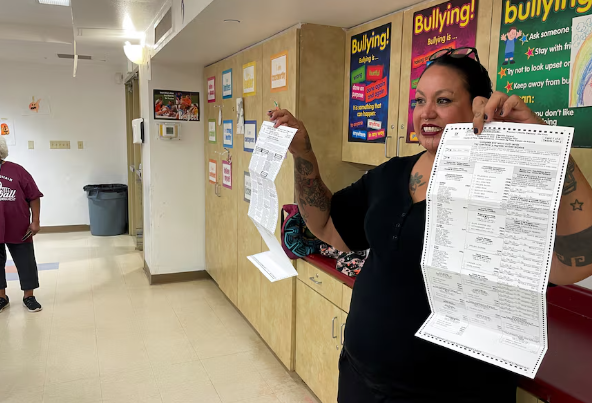

“It was really hard to vote this past primary,” said Juan, who ultimately had to cast a provisional ballot, which allows voters to record their vote while questions about their eligibility are resolved.

The Tohono O’odham Nation reservation spans a Connecticut-sized area in the Sonoran Desert, characterized by its iconic saguaro cacti and mesquite trees. Most streets lack names, and houses don’t have numbers. Many residents do not receive mail directly to their homes; instead, packages often go to a local gas station.

Native Americans represent a crucial demographic in the upcoming November 5 presidential election, where Republican Donald Trump faces Democrat Kamala Harris. The election’s outcome may hinge on narrow margins in battleground states like Arizona, home to about 400,000 Native Americans, according to 2023 census data. Nationwide, around 8 million Native Americans are of voting age, but a 2022 Biden administration report indicated they exhibit the lowest voter turnout among any ethnic group surveyed by the Census Bureau.

Voting can pose significant challenges for Native Americans, particularly the 13% living on reservations, where some residents may be over an hour away from the nearest polling place. Many lack consistent postal services, face difficulties obtaining required documents, and deal with high rates of disability. Poverty and a history of discrimination further complicate these issues.

Joseph Dolezilek, 38, from the Fort Peck Reservation in Montana, described how many residents want to register but lack transportation to the county office, which sits more than 20 miles away. “The bus runs just once a day, and you have to wait in a town you’re not from for the next eight hours,” he explained.

Both Trump and Harris have made efforts to engage Native American voters, who traditionally lean Democratic. Harris’ running mate, Minnesota Governor Tim Walz, recently visited the Navajo Nation in Arizona, while Trump has enlisted Oklahoma Republican Senator Markwayne Mullin, a member of the Cherokee Nation, for outreach to Native Americans.

In the 2020 election, Biden secured Arizona by approximately 10,000 votes, receiving about 89% of the vote from the Tohono O’odham Nation, which amounted to roughly 2,800 votes according to county records. However, two years later, Arizona Republicans enacted a law requiring documented proof of address and citizenship for voter registration. In response, the Tohono O’odham Nation joined a lawsuit claiming that the law disenfranchised 40,000 Native Americans in Arizona without formal addresses.

Despite the Republican Party’s assertion that they aim to make voting easier and more secure for Native Americans, challenges remain. A judge ruled last year that Arizona voters without a physical address could still register if they had a tribal ID card, even if it listed a P.O. Box. Registrants could confirm their home location on voter registration forms. Yet, as Juan experienced, discrepancies between identification and voter records can still lead to issues at polling places.

Jaynie Parrish, 45, a member of the Navajo Nation and founder of Arizona Native Vote, emphasized the complexity of the situation. “The problem is, it’s not easy and it’s not straightforward,” she stated.

Voting rights activists play a critical role in mobilizing Native American voters. April Ignacio, 42, explained the voting process to a group of elders during an event on the Tohono O’odham Nation reservation. As an organizer with Indivisible and a tribal member, Ignacio noted the lack of local media and reliable information sources, describing the reservation as an “information desert.”

Though she does not endorse any candidates, Ignacio provides insights about those who engage with the community. “They know what our roads look like and they know what the land looks like,” she noted.

Juan, who faced challenges in the primary, now works with Indivisible Tohono to help register voters. The group has hosted events like a “drag show for democracy” and a “Mosh the Vote” featuring tribal bands, but Juan admits they have only reached halfway toward their goal of registering 100 voters.

Residents often feel disconnected from state and national politics due to their tribal status. “We honestly live in a bubble here,” Juan said.

Gabriella Cázares-Kelly, 42, the Democrat official overseeing voter registration in Pima County, has worked to address issues like voting in the wrong precinct and confusing paperwork. She has trained staff in Tucson to recognize tribal IDs and village names and to pronounce Tohono O’odham correctly. Yet even Cázares-Kelly, who grew up on the reservation, understands the frustration some Native Americans feel.

“It’s an incredibly frustrating process,” she acknowledged. “And people are going to ask themselves, why do I bother?”